Benchmarking research takes many forms, but at its core it’s a process of test, change, re-test. At AnswerLab, we conduc...

What are research insights? What makes them different from findings?

Posted by Christina Pappas on Sep 13, 2022

At AnswerLab, we envision a world full of experiences that enrich people’s lives, and we know that these kinds of experiences stem from insights about why they think, feel, and behave the way they do.

But what exactly do we mean by “insights”? Great question! Over the past few years, the term’s been increasingly overused - it’s become a catch-all for everything from “observation” to “finding” to “idea” and beyond.

Given this, it’s no surprise that the concept of insights can feel ambiguous! So to help us wrap our minds around what insights really are, how they feel, and why they matter, let’s start by looking out - more specifically, Inside Out.

...

Pixar’s film Inside Out takes place within the mind of an eleven-year-old named Riley and creates five vivid characters out of her primary emotions: Joy, Sadness, Disgust, Fear, and Anger.

Joy, with her can-do attitude and irrepressible optimism, serves as the head honcho. Disgust, Fear, and Anger all have important roles to play: Disgust keeps Riley from being poisoned (“physically and socially”), Fear keeps her safe, and Anger ensures things are fair.

But Sadness? Her role is…less clear.

Joy - and everyone else at Headquarters - sees Sadness as purposeless at best and harmful at worst. So, throughout most of the movie, Joy strives to keep Sadness at bay out of fear that she'll “contaminate” Riley and make her miserable.

But this suppression strategy only works for so long. Riley's family has moved from Minnesota to San Francisco, and she's feeling homesick and deeply lonely. Without Sadness to serve as a conduit for self-expression, none of the emotions she has access to ring true, and she starts to shut down.

The core insight - the foundation upon which Inside Out is built - is that Sadness isn't a defect to be concealed or an annoyance to be ignored; it's a critical means of connection. Expressing feelings of sadness gives others the opportunity to be there for us, just as others' sadness inspires us to help them.

...

An insight - like the one described above - makes you feel something. It might be a jolt of recognition, surprise, or curiosity. Inevitably, it provokes a strong reaction.

At this point, you’re likely hoping for a bit more clarity. Perhaps you’re thinking something along the lines of, “Lots of things can ‘make you feel something’ - can we get more specific!?”

I empathize! Throughout my career, both as a Principal User Experience Researcher at AnswerLab and a Design Thinking instructor with UC Berkeley’s extension program, I’ve been frustrated by the fact that most insights resources stay high-level. While this is understandable - insight generation isn’t always linear, and it’s difficult to communicate an insight without the (often proprietary) context behind it - it’s not particularly actionable.

That’s why I developed a way to articulate that “WIIEE!” feeling an insight gives you - Well-informed, Illuminating, Impactful, Easy to understand, and Evocative.

-

- Well-informed: Multiple findings, levels of "why", and other pieces of evidence, e.g., researcher observations, should contribute to each insight. It should go without saying, but just in case: accuracy is a key part of this criterion.

- Illuminating: Insights must help explain or contextualize why something is (or is not) happening.

- Impactful: By definition, insights must be about something that matters; they should clearly relate to the research objectives.

- Easy to understand: Insights should be clear, direct, and memorable. They should be communicable in 1-2 sentences rather than entire paragraphs. (Of course, the evidence for them can - and should - be much more in-depth.)

- Evocative: Think of insights as diving boards into pools of exciting new ideas, directions, or possibilities. (But remember that insights are not themselves recommendations! While related, insights are fundamentally problem-centric - they shine light on a current situation, need, or issue - whereas recommendations are solution-centric.)

Tying it all together, insights - deep interpretations of what you’ve seen, heard, and sensed during your research - give you that WIIEE! feeling every time.

Breaking down the relationship between findings and insights

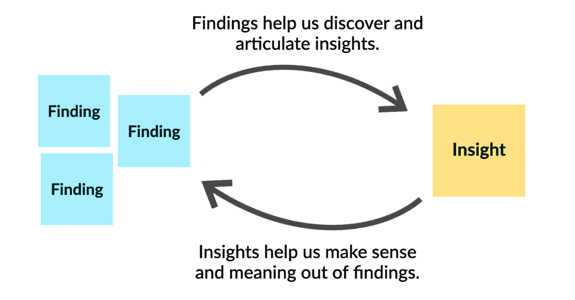

Insights have a circular relationship with findings.

On the one hand, we explore and combine findings to arrive at insights.

On the other hand, once insights are discovered and articulated, they help us make sense and meaning out of findings; they can also help tie seemingly disparate findings together by shining a light on what underlies them.

Despite their clear connection, it can’t be emphasized enough: insights are not the same as a finding (or a collection of findings)...

|

Findings |

Insights |

|

Report what happened |

Connect the dots between happenings |

|

Deal with the “what” or shallow “why” |

Encompass the deep “why” |

|

Emerge directly from explicit statements or actions |

Explain underlying motivations, beliefs, or mental models |

|

Can take a few hours of post-session analysis to identify and refine |

Can take several days of sensemaking to uncover and stress-test |

|

May be surprising in terms of results, but are unlikely to challenge existing worldviews |

Provoke a new or reframed way of understanding |

… nor are they as simple as a finding plus a “why”!

While adding an explanation for a finding almost always uplevels that finding, it doesn’t automatically transform it into an insight; this is a common misconception.

For example, take this genericized takeaway from research sessions: “When creating an account on [platform], most participants chose to use their initials rather than their full name.”

Clearly, this is a finding, not an insight: it’s an explicit statement about what happened. It’s also clear that it could be improved by addressing the rationale behind the behavior.

Imagine that we review our notes from these research sessions and find the following participant quotes (and for simplicity, imagine that they are broadly representative):

-

- "I mean, I don't really know what I'm going to be sharing [or] who else is here. Maybe I don't want other people to know that it’s me."

-

- "I don't get why other people would need to know who I am on here. I like having a little more privacy.”

-

- “I guess I just think initials are a little bit safer, like, from a privacy point of view.”

Given that, we can elaborate: “When creating an account on [platform], most participants chose to use their initials rather than their full name because they valued their privacy.”

This is a definite improvement over the original iteration. However, this new information - the “why” - did not automatically transform the finding into an insight! As you can see from the verbatims, “[participants] valued their privacy” was communicated by the participants themselves. Referring back to our table, anything that emerges from explicit statements or actions is a finding, not an insight. (That said, digging more deeply into why participants valued their privacy, or what they feared might happen if it wasn’t protected, might have resulted in an insight.)

A caveat: insights are not ‘better’ than findings!

With all this focus on insights - both within this article and across the field of UX research - it can be easy to conclude that insights must be inherently superior to findings. Not so! Different research objectives call for different outcomes.

Just like it makes sense to answer “What’s two plus two?” with a number and “What’s your favorite color?” with an option from the rainbow, it’s logical that evaluative research questions are normally addressable with findings, whereas generative ones often require insights.

In evaluative research - research to assess the current state of a product or service and whether it meets users’ expectations and needs - you typically know exactly what you’re looking to learn. Success comes from accurately answering questions like, Did users understand [X]? How did they engage with [Y]? Did they enjoy the experience of [Z]? In these cases, well-crafted, evidence-based findings are almost always sufficient.

On the other hand, generative research is all about gaining a more nuanced understanding of a situation, problem, or need; “unknown unknowns” are far more common in this type of research, and accordingly, “a deeper interpretation or understanding” is often necessary.

Insights require substantial investment of time, energy, and focus. It’s important to be sure you’re investing appropriately.

To learn more about AnswerLab's approach to uncovering insights, get in touch with a strategist.

Christina Pappas

Christina, a member of our AnswerLab Alumni, was a Principal UX Researcher at AnswerLab focused on generative research. She also teaches Design Thinking and UX Strategy through UC Berkeley’s Extension program. Christina may not work with us any longer, but we'll always consider her an AnswerLabber at heart!related insights

Get the insights newsletter

Unlock business growth with insights from our monthly newsletter. Join an exclusive community of UX, CX, and Product leaders who leverage actionable resources to create impactful brand experiences.